On This Page

- Rendering Links ...

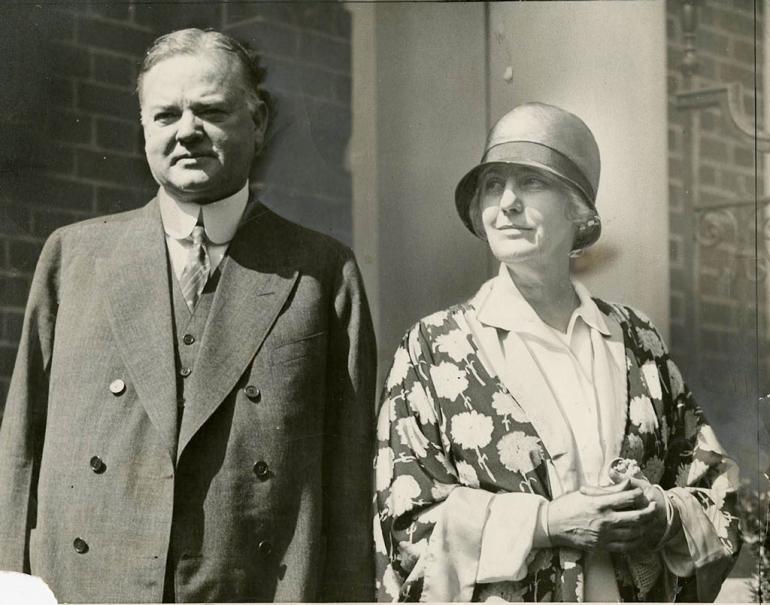

President Herbert Hoover

Early Life

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874–October 20, 1964), mining engineer, humanitarian, U.S. Secretary of Commerce, and 31st President of the United States, was the son of Jesse Hoover, a blacksmith, and Hulda Minthorn Hoover, a seamstress and recorded minister in the Society of Friends (Quakers). Hoover was born in West Branch, Iowa, where he enjoyed fishing in the local creek and working in his father’s blacksmith shop.

Hoover lived in Iowa only for the first decade of his life. Orphaned at nine years old, he began an odyssey that would make him a multi-millionaire, international humanitarian, secretary of commerce, and President of the United States.

He left Iowa at age 11 in November 1885, bound for Oregon and the home of his maternal uncle, Henry Minthorn, who was a doctor and a school superintendent, and later, a real estate broker. Hoover lived with the Minthorns for six years; at 14, he left school to work as a clerk in his uncle's real estate business. Three years later, having decided to pursue a career as a mining engineer, Hoover sought to resume his studies and applied to a new school, Leland Stanford Junior University, set to open in 1891.

It was at Stanford that he made lifelong friends, found a mentor in Professor John Caspar Branner, and met his future wife, Lou Henry. He was active in extracurricular activities, serving as student body treasurer and as manager of both the baseball and football teams.

Mining Career and Public Service

Hoover graduated from Stanford in 1895, and then made his fortune as an international mining engineer and financier over the next two decades. In 1914, Hoover was living in London when World War I broke out in Europe. Yearning for an opportunity for public service, he immediately organized assistance for American travelers who were fleeing the war. A few weeks later he established the Commission for Relief in Belgium to provide food for Belgian civilians trapped in the war zone.

In 1917 the United States entered the war, and Hoover, now a famous humanitarian, returned stateside to be appointed by President Woodrow Wilson as the head of the new U.S. Food Administration. Under Hoover’s leadership, the Food Administration dramatically increased farm production by influencing market prices with massive government purchasing, and appealed to the general public to voluntarily reduce consumption without resorting to rationing. When the war ended in 1918, Hoover returned to Europe as director-general of the American Relief Administration to distribute food and relief supplies throughout Europe.

As a result of his humanitarianism, Hoover was widely admired in the United States and was sought by both political parties as a candidate for President in 1920. Hoover eventually declared himself a Republican and accepted President Warren Harding’s invitation to serve as Secretary of Commerce. At the Department of Commerce, where he served through both the Harding and Coolidge administrations, he established a wide range of standards for manufactured products, campaigned against waste and inefficiency in industry, and encouraged the growth of new industries such as radio and aviation. He became one of the most prominent men in Washington, and his reputation as “master of emergencies” reached new heights in 1927, when he took charge of relief efforts following floods on the Mississippi River.

Presidency

In 1928, when President Coolidge chose not to run for another term, Hoover easily won the Republican nomination despite never having held an elected office. In the November election, he defeated Alfred E. Smith, the Democratic governor of New York, in a landslide.

As President, Hoover had hoped to govern in the progressive tradition of Theodore Roosevelt. And true to his dream, he devoted the first eight months of his Presidency to a variety of social, economic, and environmental reforms.

After the stock market crash of October 1929, President Hoover sought to prevent panic from spreading throughout the economy. In November, he summoned business leaders to the White House and secured promises from them to maintain wages. Hoover ordered federal departments to speed up their construction projects as a way of creating jobs, and asked state governors to expand their public works projects. He requested Congress approve a $160 million tax cut while doubling spending for public buildings, dams, highways, and harbors. The President would not, however, provide direct federal relief to the unemployed.

Economic conditions improved in early 1931 until a series of bank collapses in Europe sent new shockwaves through the American economy, leading to additional lay-offs. President Hoover was criticized for almost every program he proposed. His public works projects, designed to create jobs, were characterized as wasteful government spending. His efforts to promote local relief programs and private charities, rather than asking Congress to create nationwide relief programs, were viewed as callous disregard for the unemployed. His programs proved inadequate, as the number of unemployed workers increased from 3 million in 1930 to 10 million in 1932.

In January 1932, Hoover established the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to make emergency loans to businesses and state relief programs. Hoover also persuaded Congress to establish Federal Home Loan Banks to help protect people from losing their homes. Despite signs of economic improvement, the President’s political reputation as the “master of emergencies” plummeted in the face of rising unemployment. He nonetheless mounted a vigorous campaign for reelection in 1932 and traveled the country by train, defending his policies at every stop. But it came as no surprise to Hoover that he lost to Franklin D. Roosevelt in the general election. Hoover departed Washington with a heavy heart on March 4, 1933.

Post Presidency

Hoover devoted the next 12 years to writing books, speaking on issues of public concern, and serving as chairman of a number of philanthropic organizations. He became staunchly opposed to Roosevelt’s New Deal policies. During World War II Hoover remained on the sidelines, as Roosevelt refused to allow him to serve in a public role.

In late May 1945, only six weeks after Roosevelt’s death, Hoover met with President Harry Truman and the two men planned for the recovery of postwar Europe. In 1946, at Truman’s request, Hoover traveled the world to provide the President with a personal assessment of world food needs. Hoover and Truman also joined forces in 1947 on a commission to reorganize the executive branch of the federal government. The commission’s recommendations led to a streamlined, more efficient post–war government. Hoover later agreed to Dwight Eisenhower’s request to chair a second "Hoover Commission" from 1953 to 1955, but he was frustrated by the President’s apparent lack of support for the commission’s recommendations.

In addition to public service, Hoover devoted his post-Presidential years to social causes such as the Boys Clubs of America and the Hoover Institution, a research center he had established on the Stanford campus in 1919. He also published more than 40 books during those years.

Hoover’s attention returned to Iowa late in the 1950s when he agreed to allow friends and associates to construct a “Presidential library” near the site of his birthplace. Hoover insisted that the building be modest in size in accordance with scale of the other buildings in the community. The former President made his last visit to Iowa on August 10, 1962, to dedicate that building to the American people.

Herbert Hoover died on October 20, 1964. On October 25, the body of Herbert Hoover was interred in a simple grave on an Iowa hill overlooking the cottage where he was born.